This is the first chapter of my Master’s degree paper I wrote in 2022 about how technology and capitalist institutions affect music creation. While much of the paper remains relevant, there have been technological and cultural shifts within just the last few years that would likely have resulted in something much different if I were to write it today. Nevertheless, I am happy to share this version of a small portion of it here for archival purposes.

Entrepreneurialism

An entrepreneur is someone who sets out to make a profit from some type of good or service.1 The popular neoliberal connotations associated with such an individual usually involve them being the “backbone” of the modern economy and the idea of “pulling oneself up by their bootstraps” which is in truth physically impossible. The phrase’s original meaning was intended to evoke the idea of doing something absurd.2 This chapter is primarily concerned with the mindset that arises from a culture that consists of entrepreneurial ideals. Capitalism has instilled a sense of natural entrepreneurialism for many people, starting from their childhood. Simple concepts like setting up a lemonade stand or multinational bank sponsorships on public schools all infuse daily life with the sense of corporate pervasiveness. It is impossible to live a normal life without encountering these ideals, whether directly or indirectly. Due to this, it is the natural inclination for many people to commodify what they create, including their art. Beaster-Jones in Beyond Musical Exceptionalism: Music, Value, and Ethnomusicology, among many others, question the value of art once it is commodified.3 If one were to accept that music is a commodity, then one might also consider its relation to other commodities. Music and other commodities share innumerable similarities according to Beaster-Jones. They all “bear meanings, emerge out of particular sets of human needs, enable participation in ritual practices,and have pragmatic associations in social life.”4 It is through these similarities that art has been commodified along with almost every other aspect of people’s lives.

Adorno and Horkheimer in the Dialectic of Enlightenment discuss how the rise of capitalism and corporate power have changed the presentation of art. According to them, capitalist institutions have given a false identity to almost every aspect of our culture.5 The growing number of monopolized industries has unified popular notions of almost everything. The idea of art as a pretense for commercialization is not even needed anymore due to the prevalence and normalization of consumer-oriented products. The idea of creating art for its own sake is not as common as art as a commodity, referred to as content. “Content” as defined here,specifically refers to the now common internet jargon for the products of entrepreneurs, oftentimes in a digital format such as videos, visual art, written media, and music. “Content creators” are the people who would otherwise be considered artists if it were not for the saturation of consumer-ideology in digital spaces. These creators are usually self-sufficient, if one does not count their reliance on technology corporations for their output. They create art which is then repurposed for the intention of profit-making and are oftentimes self-described entrepreneurs. The financial motives that come from putting oneself into the capitalist institution’s ideal culture can be economically fruitful and fit into a production-line mentality of art-creation.

The incentives to align oneself with the cultural industry are strong. One of the examples Adorno and Horkheimer use is how broadcasting talent is absorbed by larger organizations before they get to the point where they can be successful by themselves.6 This can be applied to every artistic medium, especially music composition. There are innumerable financial pressures directly and indirectly from corporations—and more broadly, capitalism itself—that incentivize a composer to approach their art in particular ways. One of these is the composer who sacrifices the purity of the art for money, or more accurately writes “market-friendly” music. This is somewhat of an oversimplification as there are certainly composers whose authentic musical creations align with profit-oriented goals already. Milton Babbitt discusses something similar to this in The Composer as a Specialist, or more commonly known as Who Cares if you Listen. In it, he examines the different possibilities of a composer’s public and private life in terms of their music. He states that a composer can do themself a service “by total, resolute, and voluntary withdrawal” from the public world to the private one. And by doing this, “the composer would be free to pursue a private life of professional achievement, as opposed to a public life of unprofessional compromise and exhibitionism.”7 With this, he is comparing what he believes to be the advantageous effect of writing “specialized” music versus compromised and commodified music. Essentially, he advocates for music composition to be comparable to other fields of advanced research. Many take an issue with Babbitt’s perspective here, particularly since he advocates for social isolation to achieve it. Additionally, the somewhat elitist tone taken in the essay is perhaps paradoxical in some respects. He explicitly argues for music that rejects the idea of having a commodified value—which is generally a position that dismisses the hierarchical capital system—yet still wants certain music to be “specialized,” requiring people to have the knowledge necessary to understand it.

Regarding the content of profit-oriented music, there is one central theme throughout: it must not interfere or go against traditional neoliberal values. What this means is that it must ultimately serve the interests of the ideal culture according to large corporations. An issue with this is that if one were to attempt to write music that fights against the capitalist systems, their music would still reflect those same systems.8 By this logic, since it is impossible to escape the influence of capital, then the reasons for not aligning one’s art with said systems become dim. That is where the possibility of a more secure economic future lies, so it is futile to do otherwise; or at least that is what the cultural industry would want of its content creators. Additionally, an important note must be made of the conditions that culminate in composers and other artists who willingly create art with profit as a goal. The negative impacts of capitalism and economic scarcity oftentimes result in the necessary reorientation of artistic goals. The idea of scarcity as it affects modern society is concisely discussed in Kropotkin’s Conquest of Bread. In the first chapter, Kropotkin articulates the degree to which humanity is wealthy due to generations of ingenuity and increased industrialization. Yet despite the vastness of humanity’s labor output, most people do not retain the value of their wealth creation.9 Despite the age of the book, as it was published in 1892, this idea of worker’s owning the valu eof what they create is ever more relevant. Despite the millions of people without a home and hunger around the world, there are more than enough resources to home and feed everyone.10 The issue is a distribution one that derives from greed rather than a scarcity problem. Take the exploding short-term rental business for instance. Companies like Airbnb encourage property owners to rent out their second or third homes to short term visitors rather than directly selling them. This has greatly increased vacancies, disrupted the housing market, and negatively impacted marginalized communities.11 All of these issues directly impact composers just as they impact everyone else. Due to these issues among many others, some people simply do not have the economic stability to engage in artistic endeavors. Unless a potential composer has the financial stability to involve oneself in their artistic practice without considering how they will pay next month’s rent, then that individual would likely compose with the goal of earning a living, whether they deliberately choose to do so or not. Marx expected that capitalism was destined to collapse on itself. The increasing intensity of it would create the conditions necessary for the proletariat to abolish its exploitative hierarchy. In Capital: Volume I, he writes, “…the worker belongs to the capital before he has sold himself to the capitalist.”12 In other words, one is born into the system and there is little they can do about it.

Reification is in many ways, the amalgamation of all the ideas discussed in this chapter so far. Simply put, it is the concept of turning an abstract idea into something real. It is put succinctly in the Dialectic of Enlightenment: “All reification is forgetting.”13 This notion describes the loss of the original meaning behind an idea as it is turned into something else. Beaster-Jones discusses how this concept relates to neoliberal capitalism as it essentially turns “something that someone does into something that someone owns.”14 This commoditization of the human consciousness through ever-evolving abstract ideas illustrate the power of mass-media and culture.

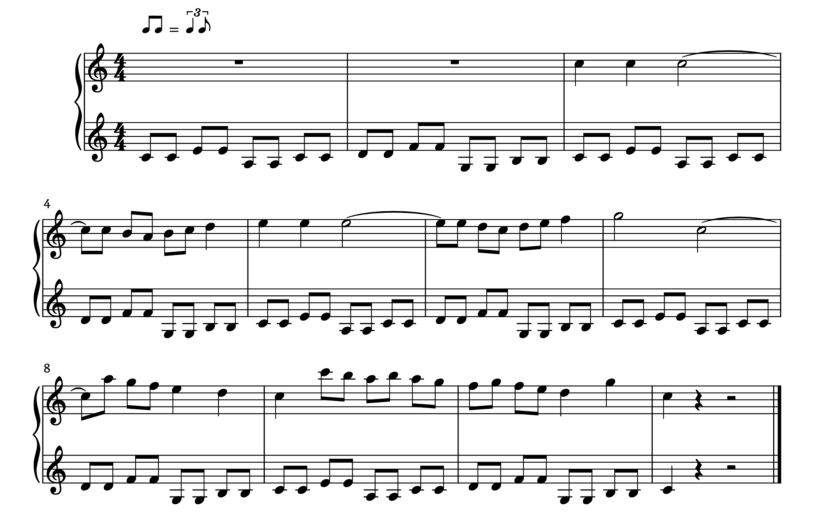

As reification applies to music specifically, one need to look no further than advertisements. One of the most common musical devices used are the re-appropriation of well-known music themes and ideas. Take an iPad mini commercial from 2012, a reduced transcription of its music in figure 1. The commercial begins with a piano app opened on a regular iPad as someone plays the bass line to Heart and Soul. As the first musical phrase concludes, the iPad mini comes into frame as another hand plays the simple melody atop the bass line.15 With this transition, the advertisement is making an effort to show an evolution with their product. There is the full-sized iPad which plays the more complex, albeit still simple bass line, while the smaller iPad plays the even simpler melody. Keep in mind that the evolution of this piece in popular culture has resulted in a much-simplified version as well. As of the date of this writing, if one were to search “Heart and Soul” on the most popular digital video platform, YouTube, then they would not find an authentic version immediately. There are many covers, remixes, and completely different songs titled the same, but anything remotely resembling an original version of this song does not appear until far into the search results. This showcases an example of distribution channel restrictions, but that is a topic for the next section.

Since Heart and Soul is one of the most well-known and popular simplified piano duets,Apple was taking advantage of how the song was generally received when the advertisement was made. The composer and lyricist Hoagy Carmichael and Frank Loesser could not have foreseen the degree to which a version of their song would be reified into what it become. Just as The Celebrated Chop Waltz, more commonly known as “Chopsticks” by Euphemia Allen become the“go-to” simple piano tune, Heart and Soul did so as well. Its place within the cultural realm of our society lies mainly as its piano version. The advertisement was technically new, but because of the music’s history, it was also a recycled version.

Reified music appears in some more subtle ways as well; it will often take the form as particular instrumentation or sound. For example, organ music has a longstanding association with sacred music. That link, alongside with the limited access to the instrument beyond churches has allowed the instrument to become associated with a sort of grand mythical quality. The same concept applies to corporate music. Oftentimes, companies will have a musical jingle associated with their brand. That music is explicitly intended to not just be market-friendly, but pro-market. It is intended to complement the company’s idea of how they should be perceived within its targeted cultural environment. It is also with the idea that that musical material will be solely attributed to the company in hopes of becoming a cultural touchstone. There have been many examples of this succeeding, notably the McDonald’s jingle for example. Due to this, it is a herculean task for many people to say “I’m lovin’ it” without thinking of that particular brand.

This direct result of the cultural industry and commodification of music has reorganized the value that is placed on art. In ‘Reification’ between Autonomy and Authenticity by Gandesha ,he succinctly summarizes this: “[culture] cannot escape the totalizing logic of commodity fetishism and reification that suffuses capitalist society in its late phase.”17 When people engage with art, no matter the medium, they must suspend their disbelief. When that art is hidden as a commodity or content, that engagement is not as fervent as it might be otherwise. Another issue arises from this when one considers the political component that comes from both art and content. As discussed earlier, financial incentives can greatly change a composer’s approach to their art. And the power behind the capital can certainly determine the direction that a composer takes regarding style or aesthetics. There is more potential profit behind conflict-free music than that which invites complex discussions surrounding class, race, gender, disabilities, and other potentially controversial subjects. Unless it is determined to be financially viable, corporate music will generally be without conflict to appear welcoming to what is deemed to be the largest possible audience. Oftentimes, this music is warmly accepted, especially by a population that is already under stress. This music can potentially distract people them from their oppressors and their disenfranchisement.

The production-line entrepreneurial mentality as discussed in this section is one of the most substantial influences on modern life. Due to globalization, it is pervasive throughout the world in almost every culture.18 Composers are not alone by how they must deal with these issues; however, they are in a somewhat unique position regarding their role as an artist and the resulting pressures they face.

Distribution Channels

When one thinks of some of the largest platforms for sharing and distributing digital art, including “content” as defined before, websites such as YouTube, Twitch, DeviantArt, SoundCloud, and TikTok come to mind among others. Interestingly, many of these are primarily video platforms as well. Due to the combination of visual and auditory components in a video, there are many varieties of such art that is shared on these platforms. Videos, still-photos, music, audio-narration, and many combinations of these are all possible on such platforms. The diversity in types of art that can be shared on them have likely been a factor in their success. For example, TikTok was originally marketed as a music-video platform where people could lip-sync to their favorite songs. However, over time, it was used in different ways to where it now serves multiple purposes for its users.19 The popularity of a platform such as it creates not only a medium for artists to share their work, but it also dictates how they do so through time limits an other restrictions. One might ask then, if it would be better for an artist to distribute their art elsewhere. This is certainly an option, however the popularity and large preexisting user base of platforms such as those mentioned provide a large incentive to use them. Publishing one’s music solely to their website can be successful if the composer is already well-known. For most composers however, the use of these platforms allows for a greater possibility of reaching more people. The main issue with this is that it is putting one’s art into the control of an external entity that may not have the best interest of the art in mind.

Steve Jones in Music and the Internet separates the relation between technology and music into a few categories: “music making (production), music consuming (consumption), and music distributing (distribution).”20 This section will follow these same categories outlined by Jones. Regarding distribution, this indicates any medium by which music is shared, which is separated into two further categories: digital and traditional. Digital distribution channels are those which are directly impacted by the technological developments within the last few decades, particularly those by “big tech.” The impact of these developments cannot be overstated. With the advent of mass communication through the internet, it was suddenly much easier for composers to share their music beyond their local reach. This was a beneficial change for artists, but not without its costs. As the internet grew, new methods of sharing and receiving music waxed and waned. Audio sharing services such as Napster bypassed the otherwise corporate hold on the music industry and allowed for easy access to music for its users—notwithstanding the moral issues regarding artist payout.21 Although it must be noted that out of the popular music streaming platforms today, Napster pays artists the most per stream. 22 Yes, it still exists.

The previously centralized music industry has now become decentralized with more options for consumption and distribution, albeit deceptively for the latter. The use of “the cloud” and mobile devices have changed music storage. Instead of the need for music to be downloaded, it only needs to be temporarily streamed.23 Because most people listen to music through streaming services over directly purchasing their music—digitally or physically—it puts a composer at a disadvantage in sharing their work if they do not allow their music on those platforms.24 Or at least, the financial rewards for their cultural product would be diminished. This is also just regarding recorded music. Composers often share their work in other ways such as sheet music or tied to another medium like films or video games. The revenue streams from these different mediums of music distribution differ, but they are all inexorably tied to the limitations of their mediums, some more than others.

Today, the consumption of music is generally associated with recordings rather than sheet music. The recorded music market is much larger than the sheet music one, which in part is why recording distribution is much more tied to technology corporations as opposed to the comparatively small sheet music publishers. This was not always the case, however. Just as sound recording was beginning to become popular, sheet music was still the main way that composers disseminated their work.25 Because of the current environment, this is partly why it is necessary for a composer who wishes to be financially successful, or more accurately, financially viable, to rely on those corporations for their digital reach. As those companies are profit-oriented, they also tend to promote music they deem to have mass-appeal. Music that is more niche, such as is the case of many living composers’ music, is not as viable as more popular music. A clear example of this is how no major streaming service or recorded music provider has a system for multi-movement works. The “shuffle” feature does not take these into consideration. But again, a composer has no say or input on the type of features involved in these platforms. They can choose to use different platforms, however all the ones with a large user base have similar issues for artists. This is an illusion of choice in some respects. For a large service intended for the distribution and consumption of music, the artists who provide its “content” should have more say in how they are designed, as well as more control over the financial payout. A cooperatively artist-owned music distribution service is necessary for these changes to occur.

The recent development of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) in decentralized blockchains has begun to change the digital art landscape. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin discusses the effect of mass-produced reproducible visual art.26 In addition, he considers the idea of ownership and changes in ownership. Different methods could be used to trace the authenticity of art such as chemical and physical analyses.27 These ideas are in direct relation to NFTs in many ways. Non-fungible tokens are essentially uniquely identifiable blocks of data that can be associated with digital transactions. Instead of physical analyses processes to determine an authentic version, a blockchain transaction is used. They have been recently associated with art and music, essentially “verifying” authentic versions of the art, in spite of the fact that there are no distinguishable visual differences between duplicates. Mass-produced art as envisioned by Benjamin and NFTs share a similar quality with every other cultural product: they rely on the perceived value that are given to them by society. A composer’s place in these matters differs slightly than the visual arts—the medium mainly pertinent to Benjamin’s essay—in that there is not a physical object, assuming recorded music.

This brings up the question of what the definitive or authentic version of music is to the artist themselves. Presuming the composer wrote the piece for performers with the intention of it being primarily presented to a live audience, a live performance would seem to be the most authentic version of that piece. As soon as there is any recording, there are many more factors that go into determining the digital version. Recording engineers are, in a way, a co-composer for the recording as the decisions they make can dramatically alter it. Benjamin discusses something like this, except in relation to a camera and an actor. He states that “the audience’s identification with the actor is really an identification with the camera. Consequently, the audience takes the position of the camera; its approach is that of testing.”28 This is applicable to recorded music, albeit to a smaller degree as visual recognition is generally superior to auditory recognition.29 The microphones, specific mixing parameters, limitations of playback, and many of elements will change how the music is perceived in a recording. However, the intention of the composer seems to go by a case-by-case basis. Perhaps to some, the score itself is the piece and any performances or recordings of it are already inauthentic versions of the source.

Up until now this chapter has mainly focused on digital distribution channels, and for good reason. The internet is perhaps the most important resource for a composer to share their art with the most amount of people possible. However, one must not neglect traditional performance spaces as well. For many student composers in particular, live performances can be more personally fulfilling than digital distribution. Not to downplay the importance of digital distribution, but the experience of having a live performance with real performers and an audience is entirely unique. For composers with the privilege of attending an academic setting, these live performance opportunities are often common. For composers outside of the traditional academic setting or composers who have left that setting, arranging such live performances can be more difficult, especially if the goal is to have them in traditional performance spaces.

Traditional performance spaces in this context refer to concert and recital halls designed and intended for the performance of concert music. The infrastructure and acoustics of these settings can often enhance performances, so access to them can be important for a composer. Unfortunately, outside of academic settings, access to these spaces can be financially prohibitive. And when a composer does have the opportunity for a live performance in such a setting, it is oftentimes with a preexisting ensemble with expectations regarding the music. These expectations may be stylistic, time-restrictions, or a variety of other particularities. None of these are inherently bad for a composer, but they nonetheless affect the creative process. With some of the more institutionalized music organizations such as major orchestras, these restrictions may be even more stringent. They are essentially organizations with the need to appeal to donors and amass-audience, so the music they select will oftentimes directly align itself with corporate power.

In Marianna Ritchey’s Composing Capital, she mentions Mason Bates’ music and its tie with technology corporations specifically.30 She points out how the electronic beats in his orchestral music allow the orchestras that perform his music to brag about their programming of“new” and “revolutionary” music, yet is still deeply rooted in the glorification of “big-tech.” She also discusses the role of “innovation” within the music industry. Because innovation requires continuous change, it forces individuals to continuously adapt to new technologies and methods of doing things. Since innovation is so entrenched in our culture, it is seen as inevitable. If an idea or “product” works for its desired goal, it is no longer beneficial to the capitalist system by which it was produced by. Innovation, genuine or falsely fabricated, is partly an imaginary for corporations to market something “new!” and “revolutionary!” whether it is or not. Therefore, a composer might be at a disadvantage at getting their music programmed by music institutions if it is not perceived as innovative. Nontraditional performance spaces have also always existed, although they have also been looked down upon as “lesser” or “unprofessional” by those who do have easy access to traditional performance spaces. This essentially restricts the possibility of art creation to a large segment of the population. When they do not outright stop people from art creation, they do create a multi-tiered system that legitimizes some performance spaces and delegitimizes others regardless of the quality of the art. The origin of Jazz for instance is the quintessential example of this. Maureen Anderson points to some racist rhetoric in the early days of jazz that said it was “dangerous, unhealthy, or, even worse, a form of bayou voodoo.”31

A final note must be made of historical trends in patronage and the associated temporal restrictions. Historically, composers have written music for the church, the royal court, opera, ballet, friends, colleagues, academia, themselves, and for many other reasons. The time period and geographical location of a composer has determined many of these for them, or at least the options available for them. For instance, a composer who lived in 15th century France would have never been given the opportunity to write an opera just as a current living composer is also not likely to write for a royal court.

Academic System

Finally, it is important to mention the impact that organizations that are not strictly corporate have on the creative process, primarily the educational system. These types of pressures originate from a few different sources including academic institutions and professional development events.

The barrier of entry or restricted access to such programs allow for a two-tiered system in some respects. The application and interview process for many music composition degree programs is well-intentioned but has some issues that restrict access. Application fees and travel costs can be financially prohibitive to many, not to mention the rising tuition costs in the United States. According to the Education Data Initiative, as of January 2022, “the average cost of college in the United States is $35,331 per student per year.” 32 And for prospective composition students that come from low-income households, attending a school for their artistic field can be impossible without comprehensive scholarships. However due to limited funding, those comprehensive “full ride” scholarships are selective, if not impossible at many institutions. It is also worth noting that many prospective students who come from underprivileged families maybe more inclined to pursue a non-artistic field in hopes of a more secure financial future. According to a Department of Education 2019 report, 39% of students within the lowest fifth of socioeconomic status attended a four-year institution versus 81% of students in the highest fifth. 33 Simply put, a prospective student with the luxury of financial freedom has much more flexibility with their future career.

For those who gain access to the many benefits of a collegiate music program, their peers will also generally come from higher-income households and have had a more advantageous childhood development than those who do not attend for reasons described above. The social “bubble” that forms inside such an environment that is restricted can also lead to particular perspectives that impact the creative process. Likewise, the opposite can occur with the composers who do not follow a traditional education path.

The variety of ideas and approaches to composition within the traditional academic system push and pull a young composer in many directions and how they might engage with their work. There is the social aspect to this which will be discussed in chapter two, however the influences from classes and mentors also impact the process. Specific assignments, available ensembles willing to play new music, and other pressures direct a composer along a specific path. This path may include writing for specific ensembles, in a particular musical style, or with a particular process. For doing the composition assignments, one is awarded with a letter grade, and at some point, a degree. However, this somewhat transactional relationship is a bit simplified, as many of the benefits of a collegiate education are more abstract such as the experience of working with performers and networking with other artists.

Additionally, these pressures are present in academic adjacent settings such as composition festivals and conferences. These have similar application processes to universities, however, are mostly available to anyone who wants to apply regardless of their educational status. Despite being available, most participants in these events are currently in or were in an academic institution. This may be due to a variety of factors, particularly a common denominator within academic circles on what is acceptable or not. There is also the potential for a disproportionate amount of music written for the ensembles that hold such calls. Finally, the influences from academia on a composer are perhaps the most malleable of the pressures discussed in this chapter. Unlike strictly corporate institutions, academic settings are designed for study and growth. This allows for deeper research and understanding of the creative pressures within such settings.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, The Theory of Business Enterprise (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912, 36). ↩︎

- Nimrod Murphree, “Pull up by the Bootstraps”, The Vermont Courier, 1834. ↩︎

- Jayson Beaster-Jones, “Beyond Musical Exceptionalism: Music, Value, and Ethnomusicology,” Ethnomusicology58, no. 2 (2014): 334–40. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Adorno and Horkheimer, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in The Dialectic of Enlightenment. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Milton Babbitt, “The Composer as a Specialist,” High Fidelity 5, no. 2 (February 1958): 38-40.10 ↩︎

- Adorno and Horkheimer, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in The Dialectic of Enlightenment. ↩︎

- Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread, (New York and London: The Knickerbocker Press, 1906). ↩︎

- Eric Holt-Giménez, et al. “We Already Grow Enough Food for 10 Billion People … and Still Can’t End Hunger.”Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 36, no. 6 (2012): 595–98. ↩︎

- James A. Allen, “Disrupting Affordable Housing: Regulating Airbnb and Other Short- Term Rental Hosting in New York City.” Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law 26, no. 1 (2017): 151–92. ↩︎

- Karl Marx. “Chapter 23: Simple Reproduction,” In Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, (London: Penguin, 1992). ↩︎

- Adorno and Horkheimer, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in The Dialectic of Enlightenment. ↩︎

- Jayson Beaster-Jones, “Beyond Musical Exceptionalism: Music, Value, and Ethnomusicology,” Ethnomusicology 58, no. 2 (2014): 334–40. ↩︎

- Cult of Mac, “iPad mini Commercial,” YouTube video, October 23, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uFUSVaqSaxQ. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Samir Holt-Gandesha, “‘Reification’ between Autonomy and Authenticity: Adorno on Musical Experience,” in The Spell of Capital: Reification and Spectacle, ed. Samir Gandesha and Johan F. Hartle (Amsterdam: AmsterdamUniversity Press, 2017): 37–54. ↩︎

- Thom Brooks, “Globalization and Global Justice,” Public Affairs Quarterly 28, no. 3 (2014): 193–96. ↩︎

- Marlowe Granados, “I Turn My Camera On: Notes on the Aesthetics of Tiktok,” Baffler Foundation 54 (2020): 99. ↩︎

- Steve Jones, “Music and the Internet,” Popular Music 19, no. 2 (April 2000): 217. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/853669. ↩︎

- “Napster Humming Along on Most Campuses,” ASEE Prism 10, no. 4 (2000): 7. ↩︎

- “Market Intelligence for the Music Industry,” Soundcharts team, June 26, 2019, https://soundcharts.com/blog/music-streaming-rates-payouts. ↩︎

- Martin Scherzinger, “From Torrent to Stream: Economies of Digital Music,” Transposition, no. 6 (December 2016). ↩︎

- “National Tracking Poll #200119: Crosstabulation Results”, Morning Consult and Hollywood Reporter, January 9-11, 2020. ↩︎

- Reebee Garofalo, “From Music Publishing to MP3: Music and Industry in the Twentieth Century,” American Music 17, no. 3 (1999): 319. ↩︎

- Walter Benjamin and Harry Zohn, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 2012). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- M. Cohen, T. Horowitz, and J. Wolfe, “Auditory Recognition Memory Is Inferior to Visual Recognition Memory,” Journal of Vision 9, no. 8 (2010): 568. ↩︎

- Marianna Ritchey, “One: Innovating Classical Music,” in Composing Capital: Classical Music in the NeoliberalEra (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 21–57. ↩︎

- Maureen Anderson, “The White Reception of Jazz in America,” African American Review 38, no. 1 (2004): 135–45. ↩︎

- Melanie Hanson, “Average Cost of College and Tuition,” Education Data Initiative, January 27, 2022, https://educationdata.org/average-cost-of-college. ↩︎

- Joel McFarland, et al., The Condition of Education (Washington DC: U.S. Department of Education, 2019), https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019144. ↩︎